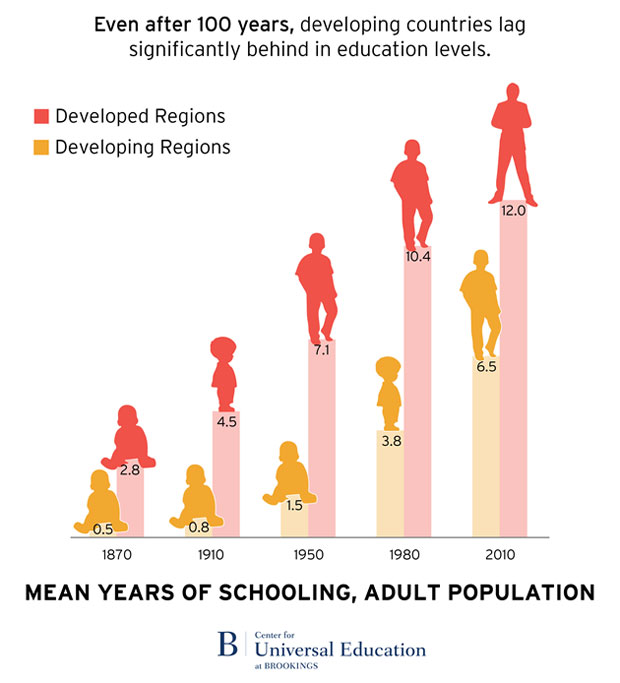

Education standards in developing countries are 100 years behind those in the developed world.

According to a new report by The Centre for Universal Education (CUE) there is a “massive gap” between developing and developed countries in both average levels of attainment and the number of years spent in school.

Writing for the BBC, Rebecca Winthrope, director of the centre, claimed: “When it's shown as an average number of years in school and levels of achievement, the developing world is about 100 years behind developed countries. These poorer countries still have average levels of education in the 21st Century that were achieved in many western countries by the early decades of the 20th Century.”

In the developed world adults spend an average of 12 years in education. That’s compared with 6.5 years in developing countries, and just 5 years in low-income countries.

(The ‘developed world’ is defined by the UN as Europe, North America, Australia and Japan)

CUE predicts that at current levels of progress it will take at least 65 years for adults in developing countries to reach 12 years of school. This gap becomes 85 years for adults in low-income countries.

However, when it comes to learning levels, the gap is shocking - in science in particular there is a massive 126 year difference in attainment. This means it will be 2141 before students in developing nations are at today’s developed world standard for science.

The specific gap in standards of schooling will obviously differ from country to country, but these findings raise serious questions about inequality. CUE claims that unless we improve progress globally, this gap will continue into the future.

But why is there such a difference in education standards, and what can be done to close the gap?

In the last 50 years incredible things have been achieved in enrolling children in primary education – resulting in 90% of all children now going to primary school.

This has been aided by the United Nations’ eight Millennium Development Goals, adopted in 2000. Target number two on the list was a promise that “by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling.”

However, once children are in school this “global convergence” disappears. It’s something that as an organisation Build Africa is very aware of.

For years Build Africa, and many other Development NGOs, have worked hard on improving access to education – and we are proud of what we have achieved. But we also know that unless that education is of a minimum standard, the benefits of attending school in the first place can be hard to see.

The UN’s education development goal made an assumption about quality. So, now we have reached 90% global enrolment, we need to shift our focus to attainment, and guarantee that going to school has clear benefits and value. That it’s not just day care until children are old enough to work.

Girls Walking to school in Kwale, Kenya

In areas where Build Africa works, such as Western Uganda, this lack of quality education is clear. Only 2.5% of Year 3 pupils we assessed passed a simple literacy and numeracy test, while more than half of teachers we spoke to had never been trained in age-appropriate methods.

One of the ways we are tackling this is through our Early Learning projects. Programmes like these aim to not only enrol young children into innovative ECD (Early Child Development) classes, but ensure that the quality of teaching there is of the best possible standard.

We do this because we know that children who receive a strong start are more likely to continue achieving throughout their time in school.

Build Africa is also working on improving levels of learning for groups often excluded from education. The clearest example of this is our work with girls in Kwale County, on the Kenyan coast.

Girls in this region face particular challenges, often suffering from a culture of discrimination, abuse and child marriage that stands in the way of any potential achievement in school. Many parents don’t see the value in educating a girl, because her value is limited to “wife” or “mother”.

During our research we found that just 40% of girls in Kwale were reaching their final year of primary school. In one rural school we recently surveyed, eight girls had dropped out due to pregnancy since the start of this school year.

Through two innovative projects we’re now working with families, teachers, government officials and girls themselves to change this, and learn more about the realities faced by young women in Kwale. Build Africa staff and our local partners are delivering gender rights classes, promoting girl-friendly teaching methods, and establishing positive female role models within communities. We’re also educating girls on sanitary health, and helping them identify the signs of abuse for themselves.

As an organisation we know that the context of education should always be taken into account, and if we focus only on access, progress will always be flawed.

Instead, if children receive the right kind of education, they are more likely to achieve in school. They are more likely to establish a secure livelihood, and they are more likely to one day support their own children to learn.

It’s education, not just going to school, that will empower communities to change.

If you have any questions about Build Africa's work, please email [email protected] or call +44 (0) 1892 519619